Is there really nothing more people want?

Hi, I’m Yasushi Yamamoto of the Hakuhodo Institute of Shopper Insight. The Institute, founded in 2003, specializes in studying ways to make the experience of shopping fulfilling in this age of superabundance, and shares ideas to that end with customers and the public at large. Our search continues for what triggers the act of buying, the final stage in the marketing process.

Is there really nothing more people want?

When I mention that I’m looking for what triggers people’s desire to buy, I’m often told, “Well, there’s nothing more anyone wants these days.” True, for over a decade now it’s been said that nothing sells anymore in Japan. Lately you often hear mention of how there’s been a shift in consumption from goods to services. But is that really the case? I turned to the Seikatsu Teiten database for answers. After all, I was with the Hakuhodo Institute of Life and Living until 2015 and even worked on the biennial survey myself. To my surprise, here’s what I found.

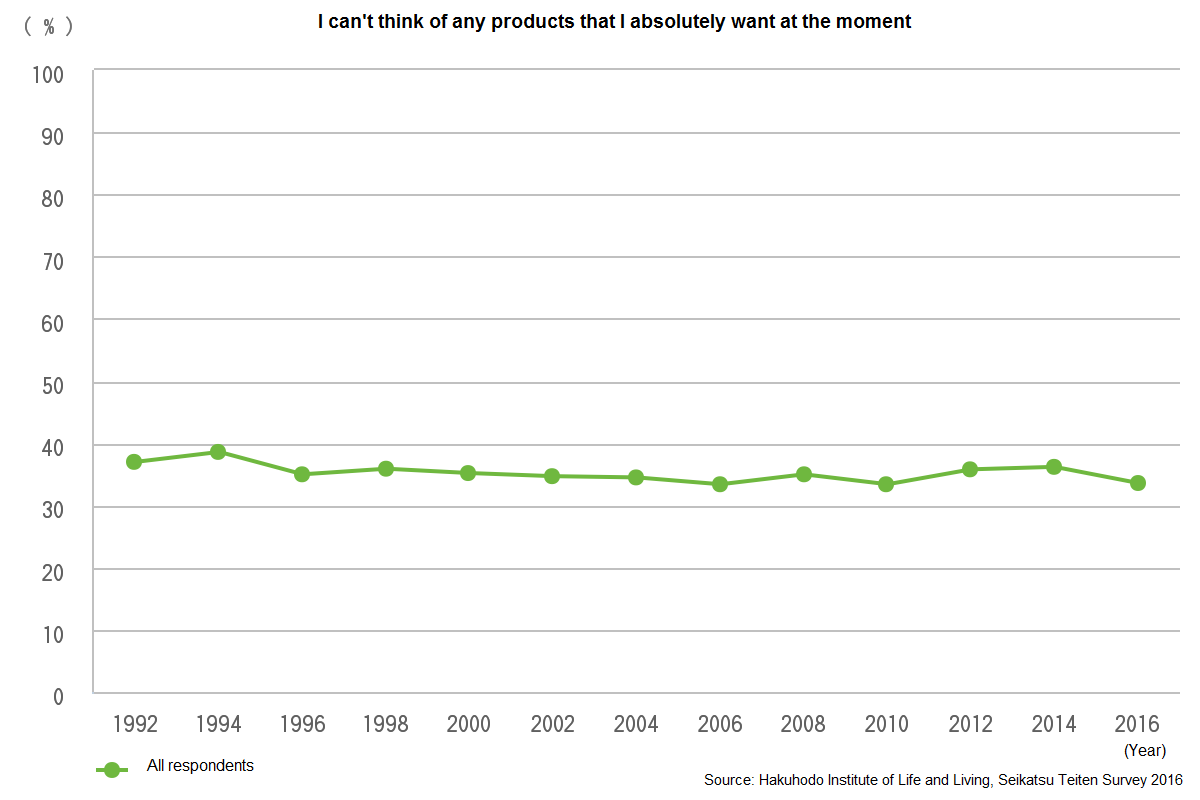

It’s not true that fewer and fewer people want anything.

The number of respondents saying there’s nothing they want hasn’t risen since the survey commenced in 1992; it’s remained steady in the 30 percent range. What are we to make of that, I wondered, when so many Japanese commentators and captains of industry take every opportunity to bewail the failure of consumers to buy? I decided to go beyond Seikatsu Teiten to examine other data on shopping patterns. Then I came across an interesting fact.

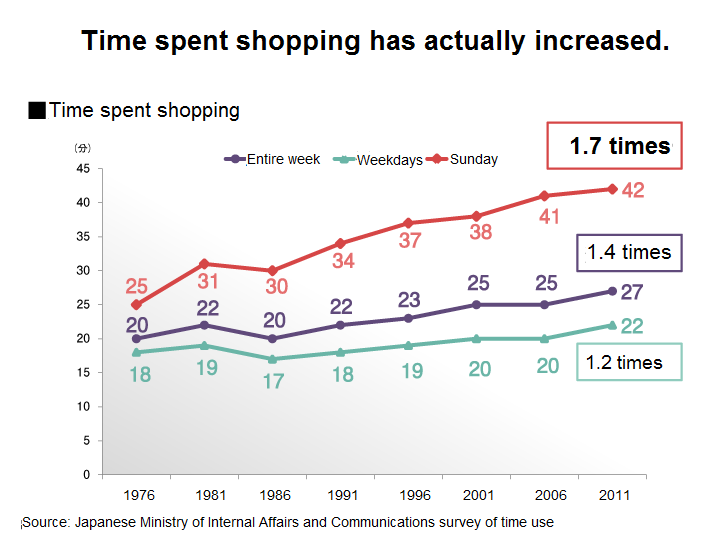

The time Japanese spend shopping has steadily increased. Especially on Sundays, it’s risen 1.7 times from 25 minutes in 1976 to 42 minutes in 2011. Far from not wanting anything, people are actually spending more time shopping. But in that case why is it claimed that nothing sells anymore? After cudgeling my brains I came up with this hypothesis: maybe people want stuff and take the time to look for it, but that fails to translate into actual purchases.

Wanting something no longer leads straight to buying it.

As often pointed out, access to information has increased dramatically since the turn of the century. Especially with the rapid spread of the smartphone in the present decade, we’re constantly staring at our devices and being bombarded by information. Even if we do have a desire for something, that desire is swept away by the constant deluge of information and stimuli to which we’re exposed. The desire itself disappears before we can act on it by making an actual purchase. So I speculated.

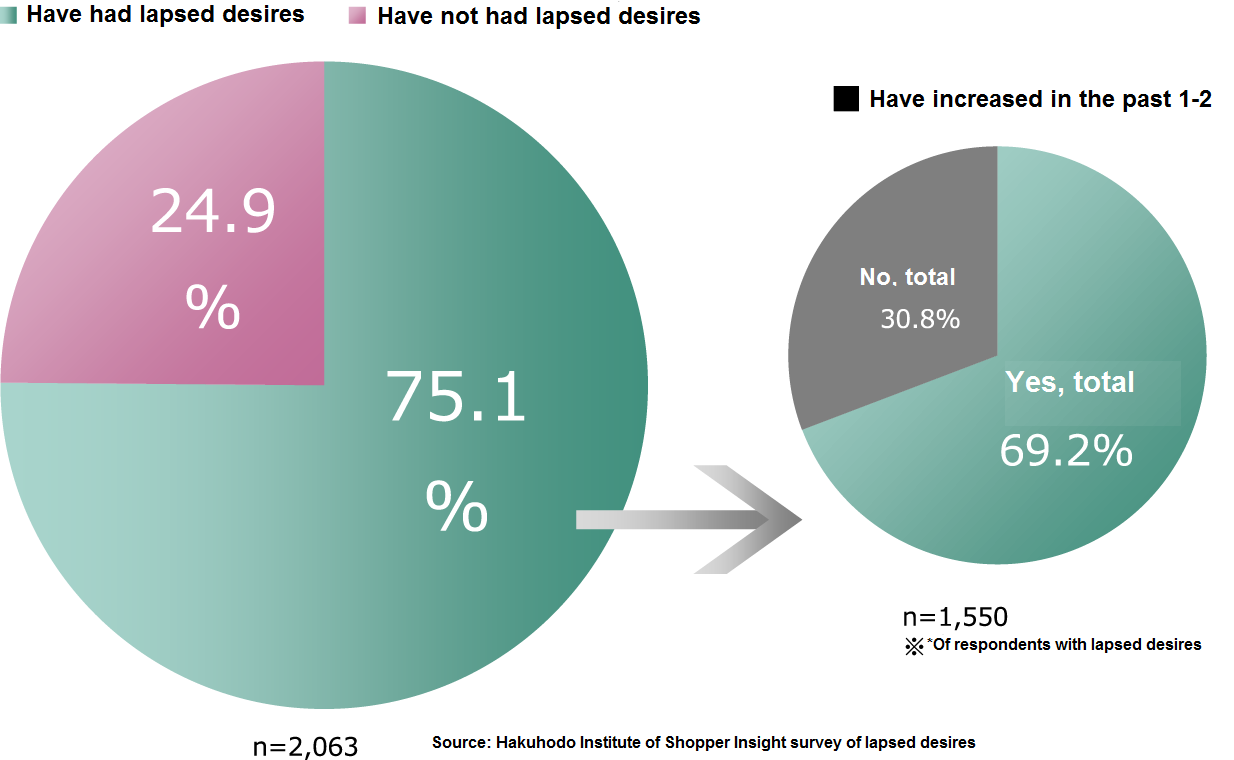

Here at the Hakuhodo Institute of Shopper Insight we termed this hypothetical phenomenon “lapsed desire.” To test whether the lapsed desire hypothesis was correct, we asked people up and down Japan whether, over the past six months, they had wanted a certain product but then at some point forgotten about or lost interest in it. Our survey found that 75 percent of people nationwide had had lapsed desires. What’s more, some 70 percent of those with lapsed desires felt that such desires had increased in the past year or two.

People have the desire to shop and devote a certain amount of time to it, but something hinders them from taking the final step and actually buying. What’s the reason for such lapsed desires?

Online reviews, far from being helpful, have become a source of stress.

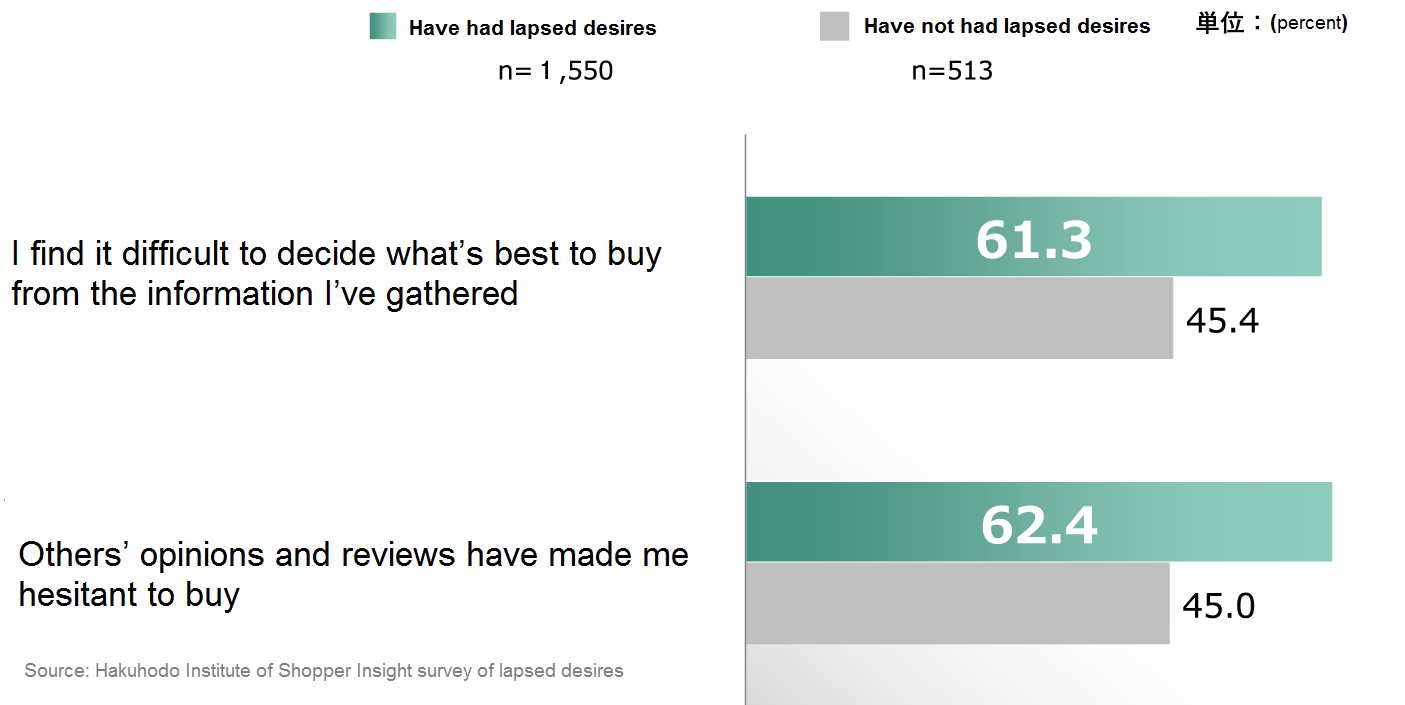

Further investigation revealed that the proliferation of information and products has made shopping itself stressful. Three points stood out when we examined the shopping attitudes of people with lapsed desires. First, online reviews and other information that they once found helpful now discourage them from buying. Those who have lapsed desires are more likely to say they find it difficult to decide what’s best to buy and state that others’ opinions and reviews have made them hesitant to buy. Information previously worked to the advantage of shoppers, but when there’s too much of it, it creates stress because people can’t make sense of it all. Which information is accurate? Is it right for me? That stress stifles the desire to buy.

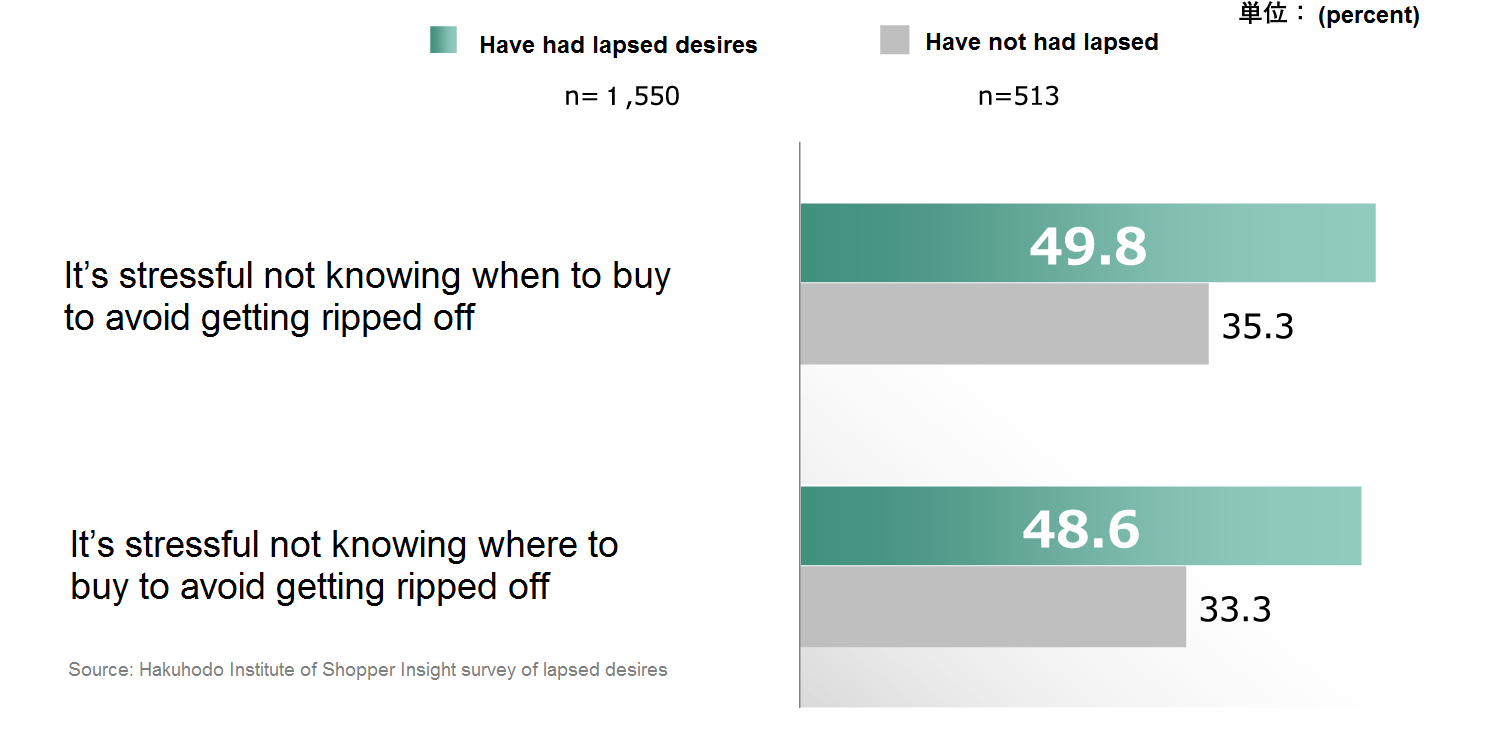

Another source of stress: exhaustive information on pricing

One form of information that has proliferated is exhaustive information on pricing. All you need to do to find out what’s available where for how much is tap on your smartphone and visit an e-commerce site. In the case of consumer electronics, you can even see exact information on the fluctuation in prices. Such information used to be handy, but with the plethora of information out there now it gets in the way of shoppers.

Those with lapsed desires are more likely to be concerned about when and where to buy to avoid getting ripped off, and feel stress as a result. Even if they want something, it may occur to them that now is not the time, which makes them think twice about buying.

People have lost sight of what they really need.

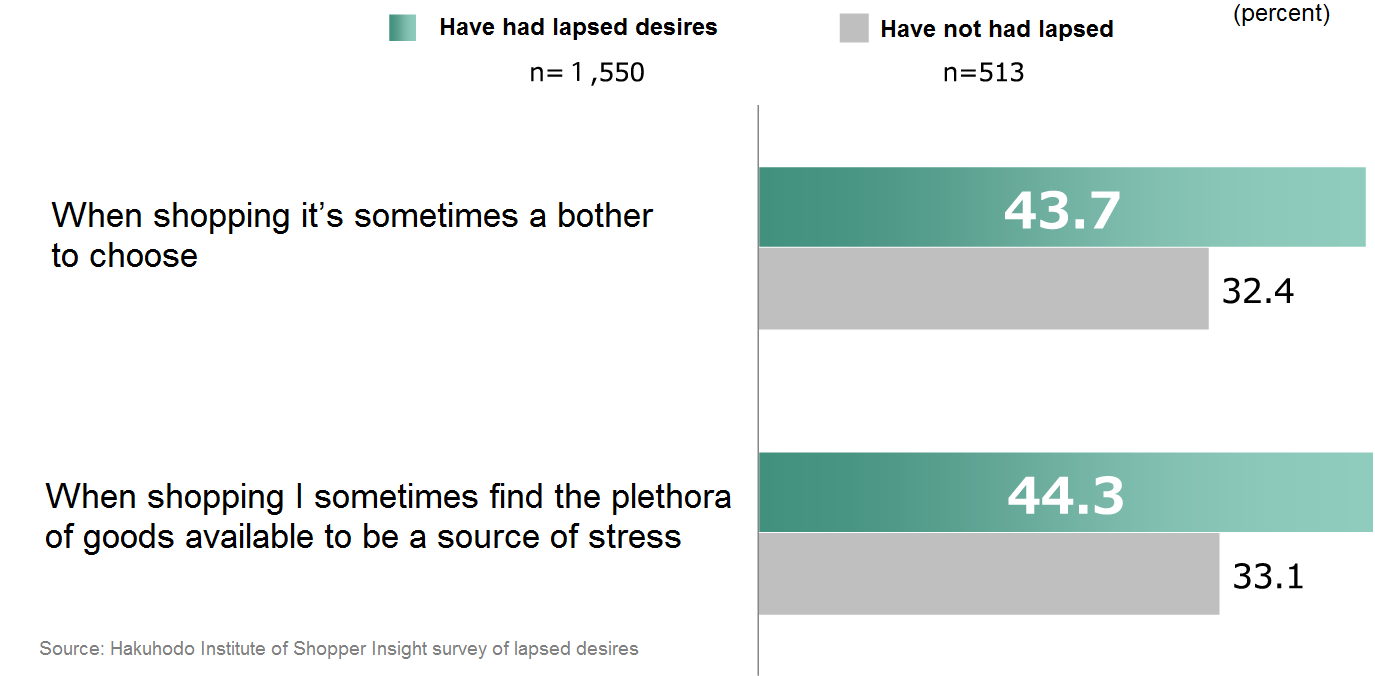

People find shopping stressful these days because they’re drowning in information: online reviews, how much things cost, where to buy. Plus there are so many products available in store. Convenience store shelves, for example, overflow with a tremendous variety of different brands, makes, aromas, and seasonal specials. During an on-site survey we conducted in a convenience store, some 80 different products were observed in the few seconds we stood in the beverages section.

This surfeit of products, coupled with the deluge of information, has made people lose sight of what they really need and unable to make up their minds. One indication of that: people with lapsed desires are more likely to say that it’s a bother to choose and they find the plethora of goods available to be a source of stress.

How should the shopping experience be designed when shopping itself is so stressful?

Ever more online reviews, exhaustive information on pricing, a vast selection of merchandise: until now such things have been seen as essential to an enjoyable shopping experience. The availability of such information on the Internet has enabled people to make smarter shopping decisions and get more for their money.

But now that people are constantly connected via their smartphones and bombarded with information, the very abundance of information and merchandise that has hitherto served them so well is deterring them from shopping. How should the shopping experience be designed in such a day and age? How do you convert the desire to buy into actual purchases? The tentative answer we propose is to make shopping more pleasurable by liberating people from the stress of shopping. We don’t, however, consider that to be the ultimate, comprehensive answer. The Hakuhodo Institute of Shopper Insight intends to continue to search for answers and share our ideas on the subject.

Examining the frequent claim that there’s nothing more people want these days in light of the Seikatsu Teiten data gets you thinking about the deeper trends behind contemporary developments. Only a set of long-term time-series data like Seikatsu Teiten allows you do that, which is what makes the survey so invaluable. Why not let the data serve as the gateway to your own intellectual journey?

Hakuhodo Institute of Shopper Insight survey of lapsed desires: Survey design

Purpose: To ascertain whether respondents have had lapsed desires, determine their attitudes to shopping and information, and identify the process whereby lapsed desires occur.

Survey sample: 2,063 males and females all over Japan aged 20-69

NOTE: Allocation by sex and age group was based on the latest demographic survey results.

Method: Internet survey

When conducted: February 5-7, 2016